Most parents are familiar with the slight panic of not knowing if you really have a way to enforce a rule you made for your kids. You’ve been clear that it is not OK to chew gum at the dinner table, but now what? Reach in his mouth and pull the gum out? Carry him to his room? Stop dinner until he complies?

Oregon is facing a similar dilemma: the Beaver state has had climate change pollution goals in law for eight years, but doesn’t have a mechanism to meet the legal pollution limits. Oregon House Bill 3470—the Climate Stability & Justice Act of 2015—would create the framework to fairly and cost-effectively phase out fossil fuels. Here’s why HB 3470 is the bill Oregon has been waiting for:

It commits Oregon to meet its existing, scientifically-based, climate pollution limits.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)—an international scientific body collecting and reviewing the work of thousands of scientists—has determined that if we want to avoid 2 degrees Celsius of warming this century, we must cut global greenhouse gas pollution 41 to 72 percent below 2010 levels by 2050. Wealthier countries that emit more must cut more to stay within our global means. Oregon could do its part by attaining its current goal of reaching 75 percent below 1990 levels by 2050.

HB 3470 would make binding Oregon’s existing science-based limits of 10 percent below 1990 levels by 2020 and 75 percent below 1990 levels by 2050. The bill requires the Environmental Quality Commission to develop an action plan for ensuring the state does not exceed its statewide emission limits.

It could create a solid cap on pollution.

Oregon is already doing a lot to cut pollution and help transition to clean energy. But no policy measure can substitute for setting a solid cap on the greenhouse gas emissions that are allowed into the atmosphere; it’s our firm guarantee that we will meet pollution targets.* A cap on pollution works kind of like musical chairs, where chairs are pollution permits and the players are tons of greenhouse gas pollution. Oregon decides how many tons of pollution (players) to allow each year and only creates that many permits (chairs). The largest emitters—about 70 coal plants, oil refineries, and large manufacturers—must buy permits in quarterly state auctions. Each year, the number of permits (chairs) dwindles, meaning fewer tons of pollution (players) are allowed. Energy companies will improve the efficiency of their operations and switch to clean fuels so they can keep delivering energy, but with fewer tons of pollution attached. Investment dollars will flow away from fossil fuels and towards clean energy solutions. Oregonians will stop sending millions of dollars to out-of-state fossil fuel companies, and instead put their money to work on clean solutions and jobs right here.

HB 3470 requires Oregon to meet its existing climate goals. The Environmental Quality Commission’s action plan may include regulations and market-based compliance mechanisms, such as an enforceable safety cap.

The cap covers all major greenhouse gases.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is the Justin Timberlake of greenhouse gases, but its old ‘N Synch band mates—methane, nitrous oxide, hydroflourocarbons, perflourocarbons and sulfur hexafluoride—deserve some recognition. In the first two decades after it is released, methane will induce 85 times as much warming as the same amount of CO2. Nitrous oxides are 268 times as potent as CO2 over 20 years. To actually cap pollution, an Oregon law needs to cover not just the heartthrob, but the whole band.

HB 3470 covers the warming potential of all six greenhouse gases.

The cap covers all major sectors of the economy.

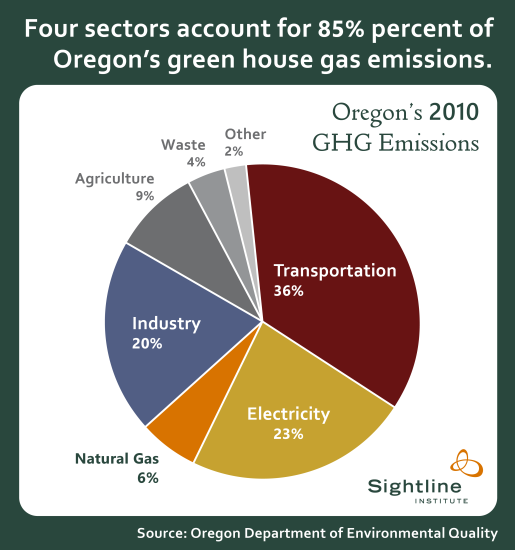

Eighty five percent of Oregon’s emissions come from four major sectors: transportation, electricity, industrial sources, and natural gas.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

By covering those four sectors, a cap can ensure Oregon hits its statewide pollution goals. Exempting one or more of these major sources would break the safety cap and Oregon wouldn’t be able to control its pollution. British Columbia, California and Quebec all limit pollution from all major sectors. But the northeast states only capped electricity emissions, so 78 percent of those states’ pollution is still leaking out, uncapped.

HB 3470 covers significant greenhouse gas emitters in every sector. The bill leaves it up to the Environmental Quality Commission to specify how big a polluter must be in order to be “significant,” but most other jurisdictions use a threshold of 25,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent per year, meaning that only very large power plants, refineries, and factories are regulated. A 25,000 MMT threshold would mean only around 70 large facilities in Oregon would be regulated—small businesses, and even big business that don’t sell or burn fossil fuels, would not have to purchase permits.

It strives for equity.

Low-income residents and communities of color are disproportionately impacted by climate change. They are hardest hit by air pollution and by economic disruption, and they have the fewest options for responding. Any attempt to address climate change in a fair and equitable manner must help these communities thrive.

HB 3470 strives for equity by:

- Appointing an environmental justice advisory committee to assist in developing the state’s action plan.

- Directing “public and private investment toward benefitting disadvantaged communities and providing opportunities for beneficial participation by small business, schools, affordable housing associations, and other community-based institutions.”

- Ensuring that programs to cut pollution “do not disproportionately impact low-income communities.”

It gets the best bang for the buck.

We urgently need to curb climate change, but that doesn’t mean we should haphazardly throw money at the problem. The most important way to avoid gold-plated pollution reduction programs is to use a cost-effective market-based mechanism, such as a cap enforced with permits. If polluters have to pay for every ton of pollution they release, they will think carefully about how to eliminate as many tons as possible by investing in efficiency retrofits and switching to cleaner fuels. Letting businesses make their own decisions about how to squeeze pollution out of their operations will result in lower-cost results than putting a public agency in charge of micro-managing business operations across the state. In addition to using a cap-and-permit system, a bill can also call out cost-effectiveness as a criterion for evaluating reduction options.

HB 3470 requires the Environmental Quality Commission to consider “market-based compliance mechanisms” and to maximize “cost-effective reductions.”

It coordinates local, state, regional and national efforts.

Local governments are taking bold climate action, Oregon is already taking action on climate on various fronts, regional fuel and power markets would benefit from a systematic western regional approach to climate, and the EPA’s Clean Power Plan encourages regional coordination to meet national climate pollution reduction goals.

HB 3470 encourages all levels of coordination. Importantly, the bill doesn’t make Oregon reinvent the wheel. Oregon already participated in creating guidelines for a regional cap-and-trade program. California and Quebec have been successfully operating cap-and-trade programs for years, and in 2014 they linked up, and now Ontario, Canada is considering joining. Oregon could benefit from joining California’s existing program, including saving itself a lot of administrative headache.

By maximizing existing climate efforts within and outside the state, HB 3470 would most effectively leverage Oregon’s efforts.

It course-corrects.

Other cap-and-trade programs have realized a few years in that they need to make some changes: better emissions data becomes available, or other circumstances changed. Without a built-in course-correction mechanism, it can be hard to revise when necessary.

A lot could change between now and 2050. HB 3470 builds in resiliency by setting new interim goals every five years. If circumstances change or new information arises, the Climate Stability & Justice Act will adapt.

Oregon could meet its climate goals with HB 3470.

Oregon’s got climate goals. HB 3470 creates a framework for fairly and cost-effectively meeting those goals.

* A self-adjusting tax that automatically changes to keep pollution reductions on target. From a policy perspective, a cap on pollution and a tax on pollution can have the same effect, but from a legal and logistical perspective, a tax in Oregon faces bigger barriers: it must win votes from three-fifths of legislators, and Oregon’s Constitution specifies that money from vehicle fuels can only be used for highway purposes.

Don Merrick

Thank you for a very thorough explanation of HB 3470. On April 8, the Oregon House Energy and Environmental Committee posted the agenda for their informational meeting on Tuesday, April 14, 3:00-6:00 P.M. in Hearing Rood D of the Oregon State Capitol. HB 3470 is on the agenda. Four distinguished guests have been invited to give testimony. Details can be found by accessing OLIS and the specific committee. I encourage all to attend this hearing to support this important bill and 2 companion bills.

Deb Evans

Excellent description of HB 3470 and the effects it can have on reaching Oregon’s greenhouse gas emission reduction goals! I was one of the many people that showed up for the hearing on April 14 filling the hearing room plus two additional rooms in support of moving a climate bill forward. Very powerful testimony was given on three bills and some of it can be viewed at: https://olis.leg.state.or.us/liz/2015R1/Committees/HEE/2015-04-14-15-00/MeetingMaterials.

As of yesterday, April 16th, HB 3470 is the only climate bill still alive and many of us think, with support, it can pass this legislative session! HB 3470 has a scheduled work session next Tuesday, April 21, and it must pass out of the Energy and Environment Committee on that day. We are urging EVERYBODY to write NOW in support of HB 3470 addressing your email to: Chair Vega Pederson and members of the House Energy and Environment Committee then send to: beth.patrino@state.or.us

Include your name and city at the bottom and CC a copy of your email to your Representative and Senator so they will know you have their back in supporting the passage of this important legislation. Thanks so much!

Benoit

Great analysis, as usual ! and… one mistake…

And I’m pleased to read that Oregon would be leaning to, like Ontario, join the California/Québec linked Cap & Trade systems under the Western Climate Initiative (WCI) North American carbon market partneship. With Ontario now joining Californa and Québec, we more than ever have a solid base for evolution towards a truly North American regulated, and rigorous, carbon market.

One important correction would be needed though in your presentation. You always say «In 2014, Quebec joined the California cap». The fact in that Québec and California designed their C&T system in partnership and they both started it at the same time, in January 2013. Then they linking their systems in 2014, under the WCI regional carbon market partnership. Moreover, that program itself has been designed in the previous years also in partnership by California and Québec AND – this is important – 9 other North American States, including Oregon and Washington State, and Ontario. So Washington and Oregon would only be joigning a C&T regional program in which they already contributed significatively to its design (see «Design Recommendations for the WCI Regional Cap-and-Trade, http://www.westernclimateinitiative.org/document-archives/general/design-recommendations/Design-Recommendations-for-the-WCI-Regional-Cap-and-Trade-Program/» )

So Oregonians(?) and Washingtonians already have reasons to be proud of that innovative and rigorously designed system that will help us all make the transition towards the economy of the 21st century !

So lets hope you’ll join us soon : )

Benoit

Climate Change specialist

Montréal, Québec

@GoEcoSynergie

Kristin Eberhard

Thanks Benoit. I added a sentence about WCI and linkage.

Thomas Dunne

Climate change must be addressed, even it is too late reducing green house gases will mitigate the level of the disaster ahead.