A tax and a cap are just different vehicles for delivering the same thing: a carbon price that holds polluters responsible for their pollution, drives the transition to clean energy, andstaves off the worst risks of climate volatility. With a tax, you know the price in advance but not the quantity of carbon pollution per year; with a cap, you know the carbon but not the price.

Could Oregon and Washington create a cap-tax hybrid that is custom-made for the Pacific Northwest’s unique circumstances, culture, and economy? Northwesterners are down-to-earth and pragmatic, resilient through changing conditions. A Northwestern climate policy should be the same: taking the best aspects of what has come before (BC’s tax and California’s cap) and hybridizing them into a robust policy that can ride out the rainy days.

This article, the first of three about variations on carbon pricing, describes not just one but four cap-tax hybrids that could fit the Northwest like a fleece vest.

1. Use a self-adjusting tax to get the pollution cutting certainty of a cap.

Oregon or Washington could combine the price certainty of a tax with the pollution-slashing certainty of a cap. A self-adjusting tax is like the bumpers at the bowling alley. You pick a tax that aims for the carbon pollution trend to go right down the middle of the lane, but if your aim was bad, the automatic tax-rate adjustments act like bumpers, nudging pollution levels back on course. In Switzerland, a crude version of this approach is the law. The nation enacted a CO2tax in 2008 and later modified it to allow increases if the nation does not hit its carbon phaseout goals. Switzerland’s2012 ordinance set the tax at 36 Swiss francs (about US$37) per ton and authorized increases to 60 francs in 2014, 72 or 84 francs in 2016, and 96 francs in 2018. The federal environment agency automatically increased the tax to 60 francs in March 2013, because Swiss carbon pollution levels in 2012 hit the trigger threshold.

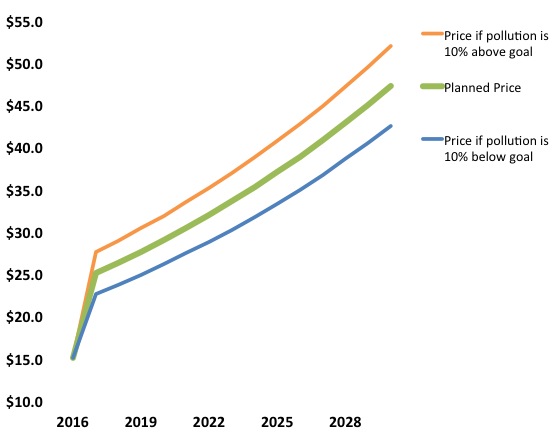

The Swiss plan has giant tax rate increases; the bumpers don’t just nudge, they whack the ball back into the lane. Oregon or Washington could implement a subtler and smoother automatic carbon tax: one with tailored, pre-determined, pollution-triggered price adjustments to ensure the state meets its pollution trimming goals. How might this work? One simple example: the planned tax rate trajectory could be like the one that CarbonWA advocates: starting at $15, then up to $25 the second year, then rising at the rate of inflation plus 5 percent per year, as California’s floor and reserve prices do. Every three years, an agency—perhaps the Department of Ecology in Washington or Oregon’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ)—would run the numbers to see whether the state is sticking to its legally mandated schedule for trimming carbon pollution. If pollution was more or less than expected, the tax rate would bump up or down by the same percentage. For example, if pollution dropped 10 percent more than expected between 2015 and 2017, the tax would automatically drop 10 percent from the planned rates for 2018-2020. It would be $24.80 per ton in 2018 instead of $27.60. The adjustments would be symmetrical, as illustrated in the chart below. If polluters spewed out 10 percent more carbon in 2015-2017 than allowed by law, the tax rate would step up by 10 percent in 2018-2020: $30.30 in 2018, instead of $27.60.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

An even more sophisticated, made-in-the-Northwest version of this bowling-with-bumpers tax might employ rate adjustments that phased in tax increases and decreases or that only adjusted the rate of change in the tax rate, rather than the underlying rate itself. For example, if there was too much pollution in 2015-2017, the tax might increase at a rate of GDP plus 10 percent per year, rather than 5 percent, for 2018-2020. It’s easy to imagine refinements.

The important point is that this self-adjusting tax rate would give everyone price certainty within boundaries. Businesses would know the exact carbon price for the next three years, and they would know the price would be within a narrow range for each three-year period after that. This knowledge would allow them to make long-term investments based on the price. It would also ensure that Oregon or Washington would actually squeeze carbon pollution out of its economy on schedule—walking down the stairs to carbon-free at a predictable, measured pace. In other words, we’d get the simplicity and most of the price certainty of a carbon tax plus most of the climate-protection certainty of a carbon cap. And it’d be a uniquely Northwest solution, taking the best of BC and California.

[table “” not found /]| Pros | Cons |

| Price certainty, within bounds. | Price might be too high or too low for a few years at a time. |

| State will meet its carbon goals. | Pre-determined price changes might not be sufficient if the original price was too far off. |

| Gets close to lowest-cost cuts. | Less certain than un-adjusting tax on price; less certain than cap on carbon pollution. |

| Motivates clean energy investments because businesses know the price will continue. |

2. Adopt a cap but authorize a tax as a backstop.

Oregon or Washington could start with a cap and authorize a tax as a fallback. The legislation would require state agencies to move forward with the regulations needed to join California’s cap, but it would also spell out a carbon tax as a backstop. It could be an extremely simple carbon tax—almost a photocopy of the rules and regulations in British Columbia, for example. That way, tax authorities will not have to do drawn out rulemaking before launching the tax.

The legislation would also specify the conditions that would trigger the state to abandon the cap and implement the tax. For example, it could authorize the state revenue agency to begin collecting the tax on a specified date unless the state environmental agency first certified it had successfully joined California’s cap and met other criteria: for example, the plan does not contain loopholes that endanger the state’s legal commitment to its schedule of emissions reductions, and that there is no evidence of destructive gaming in the carbon market. Because the tax rate schedule was already authorized in the legislation, the switch could be fast.

[table “” not found /]| Pros | Cons |

| State will meet its carbon goals. | Price would not be in place for several years while agency goes through the rulemaking process. |

| Takes advantage of the existing cap. | More complicated than a cap or a tax alone. |

| Ensures action on climate. | |

| Protects against gaming or other problems with the cap. | |

| Motivates clean energy investments because businesses know the price will continue. |

3. Start with a tax and transition to a cap.

Oregon or Washington could start a carbon tax immediately, and transition to a cap in a few years. The cap could start on the CarbonWA trajectory explained above, for example, or on a path to quickly catch up with British Columbia’s current price of $30 per ton. This way the carbon price would already be in place as the state environmental agency went through its required public rulemaking to develop a cap. Once the cap regulations were ready, the tax rate then in effect would become the floor price in the state carbon auction. There would be no price volatility, as polluters would transition smoothly from paying a tax of, for example in 2018, $26 per ton to purchasing allowances for a minimum of $28 per ton in 2019.

CarbonWA or BC’s price trajectory would put Oregon or Washington’s floor price well above California’s floor price (currently $11.34), and likely above California’s auction price (currently $11.50). The state’s allowances would sell at their (higher) floor price for a few years until the market price caught up. This would create a price discrepancy between the states, but would ensure a quick and strong price signal as well as the certainty of keeping pollution under the cap. Alternatively, Oregon and Washington could set their starter tax rates to align with California’s auction price for allowances—a slower start in pricing carbon but one that would make the transition to a cap simpler.

[table “” not found /]| Pros | Cons |

| Price certainty for years. | More complicated than a cap or a tax alone. |

| State will meet its carbon goals. |

4. Implement a tax with a cap as a backstop.

Oregon or Washington could implement a tax but keep a cap at the ready. They could pass bills that authorize a carbon tax but also direct DEQ and Ecology to prepare the regulations needed to link to California and keep them on a shelf. Every three years, the agencies would review the tax to see whether it is paring pollution as needed. If pollution cuts fell short of pre-determined milestones, the state would abandon the tax and join California’s cap. This policy would allow a fast switch from tax to cap because the agency already had the cap ready to roll. It would prod stakeholders to push for a tax high enough to wring pollution from the economy on schedule, because an inadequate tax would trigger the launch of cap and trade.

On the downside, this backstop plan would create a lot of work for the agency to write regulations that might never be used. It might even cause some businesses to not only pay the tax but also purchase allowances as a hedge against future risk. To prevent these downsides, the legislation could retain the authority to cap, without ordering the agency to write the regulations immediately. The agency would wait until the first three-year check-up to see whether the tax worked. If it did not work, the tax would stay in place while the agency went through the rulemaking for the cap. Once the rules were ready, the state would abandon the tax and join the cap.

| Pros | Cons |

| Price certainty, if tax stays in place. | Potential for wasted agency efforts. |

| Ensures action on climate. | Duplicative compliance efforts by business that pay the tax and also purchase allowances as a hedge. |

| State will meet its climate goals. |

Northwest Hybrid Vigor

Every one of these options offers some perks that a cap or tax alone doesn’t. Why stick with basic cable when you can bundle it with other services you want? Although they each could add value to the basic carbon pricing proposal, my personal favorite is number 1: the automatically self-adjusting carbon tax. It could start right away, send a clear signal that would spur immediate investments in clean energy, but elegantly course-correct to guide us to a cleaner economy and a safer climate.

The self-adjusting tax, with its calm resiliency to pollution ups and downs, is like northwesterners walking to work: we are prepared with a hood in case it pours or layers in case the sun comes out—but we’re going to get there rain or shine.

Steve Erickson

The problem I see with #1 as described is that if decarbonization is proceeding faster than planned – the most desirable outcome – the system will act as a brake and slow the process. Maybe if it were 20 years ago this would be reasonable, but it really isn’t anymore. The faster we get the carbon out the higher the probability of avoiding the worst outcomes.

Kristin Eberhard

The idea is that this would keep Washington on path to its statutory goals: reducing carbon to 50% below 1990 levels by 2050. Lowering the price would not slow Washington from getting to this goal, though it would stop Washington from going *below* its goals. It is true that the pace and risks of climate change mean we should do everything we can as fast as possible, but these scenarios are built around complying with the goals that are already enshrined in Washington law.

Wells

Cap and Trade or Cap and Tax, these elaborate monetary systems that can help transition from fossil fuels seem to have enough disincentives to prevent significant progress toward that goal. They may only apply to centralized power and fuel supply systems. Low-emission technology combined with energy conservation is the more important part of the discussion.

Decentralized fuel/power systems face opposition from international corporations. For instance, combined with rooftop photovoltiac solar array, plug-in hybrid vehicle technology can reduce fuel/energy consumption more than all-electric Nissan Leaf and Tesla. This may seem counter-intuitive, but if emission reduction can only be achieved if we drive less, fly less, truck and ship goods around the world less, local and regional economies of production/distribution must supplant the global economy. All-electric EVs lead motorists to believe routine long-distance driving is sustainable. Plug-in hybrids offer many such incentives to drive less and reduce household energy consumption.

Christin

Wells,

I completely agree that monetary incentives won’t be enough to change the energy intensive behavior patterns we are stuck in.

If you keep track of many of the other posts related to adapting to low carbon infrastructure (Oil By Rail, Bicycle Neglect, Legalizing Affordable Housing, etc.), you’ll see how these other, arguably more important, aspects of infrastructure change are even slower to come than implementing an emissions reduction plan (which is 6 years in the making).

– Housing laws in many municipalities hinder the ability of millienials to acquire sustainable living arrangements with access to land to grow food, unobstructed sunlight to support solar arrays, or permission to reduce their production of household waste (via composting) near their place of occupation.

– WSDOT has failed to require science-based safety compliance from oil trains.

– USDOT has failed to prioritize increased fuel efficiency since it’s inception in 1966.

– Washington state has been subsidizing the transportation and production of oil refined within our region because of an outdated tax loophole for 62 years.

– The WSIB is investing state revenue in coal and oil industries.

– Municipality after municipality refuses to invest seriously in bicycle infrastructure.

All of these things stand in the way of mitigating disastrous climate change and reducing our emissions as a state.

In addition, not everyone is convinced that change is necessary and we have to have a way to motivate those people to reduce emissions. Continuing to wait for these individuals to understand the ever accumulating mountain of evidence they’ve been ignoring, instead of using our economic system to mitigate the future costs of this inaction puts future generations at greater risk without greater resources.

Once we start generating money from carbon taxes, we will have the extra cash flow to make the appropriate investments in low carbon infrastructure. Of course, that’s only if it’s implemented correctly: with appropriate programs encouraging local/regional production development and investment in appropriate technologies, which remains to be seen.

Sorry if that was a lengthy path to the point. I wanted to incorporate your specific concerns, because I agree with your observations. I just think there’s a more positive way to look at this particular facet of addressing climate change by looking at how it fits into the solution puzzle.

Wells

Christin, thanks. My point was meant to address the article’s specific lack of where the funds are directed. Discussions solely about how taxes are raised can misdirect the funds. I highlighted the potential of plug-in hybrid technology as an example where to direct funds. Investing in passenger-rail is likewise a closely related issue. Too many celebrated technocrats and wannabees ignorantly promote Battery Electric EVs (Tesla/Leaf) and prohibitively high-cost all-electric 200mph high speed rail. Personally, I cannot trust an author who neglects this more imporant aspect of the discussion. Tax n’ Cap or Tax n’ Trade mechanisms may only apply to decentralized power generation. Plug-in hybrid is the more ideal match to rooftop solar and regional utility grids. 125mph High speed rail running diesel/electric (and/or raises a pantograph to run all-electric where necessary) is applicable to more passenger-rail corridors. Ms Eberhard writing from Seattle, probably advocates for ineffective transportation systems and like most Seattlers won’t consider contrary viewpoint.

Wells

edit:

Tax n’ Cap or Tax n’ Trade mechanisms may only apply to “centralized” power generation. Decentralized systems, rooftop solar, incentivize energy conservation both driving and household consumption, and make a fine backup emergency and portable power system with the plug-in hybrid.

jan Freed

A revenue neutral carbon fee with a dividend, makes enormous sense!

Economists and scientists say it is the best solution to the threat of our carbon emissions.

It is not a tax. This way citizens would RECEIVE the carbon fees as a monthly check, for example. That would protect us from price spikes in dirty energy. Polluters PAY the fees, so it holds fossil fuel corporations responsible for the damages. or externalitites, they cause, hundreds of billions of dollars per year (Harvard School of Medicine).

It would more rapidly lower emissions than regulations, as happened in BC Canada with a similar, popular policy. BC lowered both emissions and taxes with their fees.

A study by respected non-partisan Regional Economic Modeling, Inc. found the dividends would help to create 2.9 million additional jobs in 20 years, while reducing emissions much faster than regulations: a 50% reduction in 20 years.

ahttp://citizensclimatelobby.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/REMI-National-SUMMARY.pdf

To those who reject the science: perhaps nothing will change your mind. But what have you got against cleaner air, less asthma in our kids, fewer heart attacks, and more money (the dividend) in your pockets?

To those accepting the science: Any effort to limit the problem of climate change is worth it. For example: the cost of sea level rise ALONE is so great that no effort to prevent it is unwarranted.

Elon Musk was asked “what can we do? ” Musk: “I would say whenever you have the opportunity, talk to the politicians.,,,,. We have to fix the unpriced externality [social cost]. I would talk to your friends about it and fight the propaganda from the carbon industry.”