Update 8/11: I have an addendum to this post published here. Also, the chart was altered to reflect a slightly higher number for Vancouver.

What if the Northwest’s cities legally capped the number of pizza delivery cars? What if, despite growing urban population and disposable incomes, our Pizza Delivery Oversight Boards had scarcely issued new delivery licenses since 1975? Pizza delivery would be expensive and slow; citizens would rise up in revolt.

Substitute “taxicab” for “pizza delivery” and you have a reasonable facsimile of the taxi industry in Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver, BC: tightly restricted taxi numbers, high fares, and low availability.

Plentiful, affordable taxis facilitate greener urban travel. They help families shed second cars, ride transit more often, and walk to work on could-be-rainy days. They fill gaps in transit systems and provide a fallback in case of unexpected events.

In the Northwest’s largest cities, however, local ordinances enforced by taxi boards suppress the entry of new cabs onto the streets. They impose arcane and ultimately farcical management principles reminiscent of Soviet planning. Imagine teams of pizza regulators pawing through discarded receipts and pizza boxes to determine whether demand for pizza delivery markets are “oversaturated,” and you won’t be far from the truth. Restricting taxicab licenses undermines passengers’ mobility, local economies, and—by encouraging driving—our natural heritage; uncapping cabs would allow market competition to bolster all three.

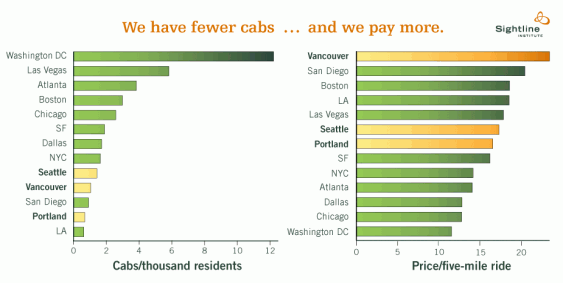

As shown in the figure above, at present, the Northwest’s largest cities have fewer cabs per capita, and higher fares, than many US cities. Seattle’s 1.4 cabs per 1,000 residents is twice Portland’s 0.7, and well above Vancouver’s 1 cab per 1,000. But all our cities lag. Washington, DC, has more than 12 cabs per 1,000 residents; Las Vegas has almost 6; and San Francisco has 2. Meanwhile, the cost of a typical, five-mile trip is $16.50 in Portland, $17.25 in Seattle, and $23.39 in Vancouver. Washington, DC’s typical fare is just $11.50.

Consider the efforts of Portland’s Transportation Board of Review, which has the power to issue new taxi licenses but is also charged by city law with monitoring “market saturation factors.” It is supposed to avoid market oversaturation, something every other market—from pizza delivery to home remodeling—manages to do just fine on its own, without benefit of a board. In Portland, the rules actually require applicants to prove that a new taxi license is needed. Imagine if Pizza Hut had to demonstrate to the Pizza Delivery Board that it needs another driver for the Super Bowl.

In Vancouver, the Passenger Transportation Board‘s rules are slightly more flexible than Portland’s. They have allowed a trickle of new cab licenses over the years, but they have screened out many applicants, too. A Vancouver cab company seeking a new license is supposed to prove the taxi market isn’t already too full, and that can be a complex question to answer. In other markets, entrepreneurs figure out the answer to their own satisfaction, then see if they’re right by risking their own time and money. New pizza parlors do not have to show city regulators that their delivery service is needed.

Worse, in Vancouver, cab companies may petition against a competitor’s new license. When Pizza Hut applies for an extra delivery license for the Super Bowl, in other words, Domino’s has a right to challenge the application. In 2010, the board rejected some 43 percent of requests for new permits, despite the city’s high taxi fares and paltry cab numbers.

Seattle’s Department of Executive Administration, like taxi boards to the north and south, tries to divine the number of taxicabs Seattle can support without oversupplying the market (whatever that means). Its method is to comb through an enormous database of “weighted average taxi response times” to look for signs that wait times are getting worse. Making the heroic assumption that Seattle’s status quo of long waits and fruitless cab hunting are acceptable, it looks for signs of further deterioration before considering new licenses.

A better test would be whether anyone is willing to pay for a taxi license. Guess what? Seattle medallions currently trade for $100,000, when they’re for sale at all. When the city offered 15 new licenses for wheelchair accessible taxis in 2009, 723 drivers applied. Vancouver taxi licenses have sold for up to CDN$500,000. (In New York, taxi medallions were selling for close to $1 million in June.) The explanation of these bubble-like prices is economics: restricting taxi supply increases the profitability of each cab. Holders of taxi licenses can fill their cabs more of the time and keep the meter running.

In the Northwest as across the continent, taxi regulation is dominated by license caps and fixed rates, but that isn’t the only way. Washington, DC, has no limit on the number of cabs. It has plenty of taxis and low prices. The capital city does regulate taxis, insisting, for example, that drivers and vehicles meet safety criteria, that fares be clearly posted, and that meters be accurate. But DC law imposes no lid on taxi licenses. That’s good sense. When we import that approach to Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver, we’ll have more-robust urban taxi fleets and we’ll be able to leave our own cars home more of the time.

Guest blogger Vince Houmes of Seattle is a longtime Sightline supporter and hobbyist policy researcher.

Sources of charts: Data from the Chicago Dispatcher, with updated city populations (from Wikipedia) and updated numbers of Seattle and Vancouver taxis. An “average trip” is 5 miles long, with 5 minutes of waiting. Per-capita numbers are for city, not metro, population. Vancouver cab prices relied on an outdated website when this post was first made. Correct prices may be found here.

Sightline’s Making Sustainability Legal project identifies specific regulatory barriers to affordable, green solutions. If you’ve come across such an obstacle, please let us know by writing Eric (at) Sightline (dot) org.

Tim Colman

Thanks for the well written piece on taxis.

This story looks like it would translate well into a Make Sustainability Legal campaign.

Where is the legislation we can bring to change the way taxis are supplied?

As long as green transit doesn’t mean low wage, I am all for it.

And where are the local mini buses that can take people in neighborhoods to shopping centers, rec centers etc…?

Best fishes,

Timothy Colman

Vince Houmes

Interesting question, Tim. Taxi policy affects everyone, but the taxi industry (and to some extent the tourism and hospital industry, the heaviest users) have the most direct interest in any legislation that would change the current system. The cab owners in particular would be materially affected if medallion caps were to loosen.

It’s difficult, but not impossible, to get people organized around a specialist topic like this. Starting the conversation is a good first step.

zefwagner

I know that Mayor McGinn in Seattle has been working on a nightlife initiative. Part of that involves making it easier for drunk people to get home without driving. Late night transit is one answer, but clearly more taxis would have even more of an impact. Perhaps a proposal to loosen these kinds of restrictions would gain public support if it was tied to reducing drunk driving.

Bill in Madison

In loosening the regulation of the taxi industry, it is critical that attention be paid to the wages and working conditions of the drivers. I know that in Austin, TX, where I lived previously, many of the drivers were barely able to scrape by (see: http://www.austinchronicle.com/news/2010-06-11/1039602/).

Alternative solutions include better late night transit, as suggested by zefwagner, or jitney service–small busses on semi-fixed routes that might be able to provide more affordable late night transportation without sacrificing the economic welfare of the drivers.

Alan Durning

Thanks for the Austin link, BiM. It’s fascinating. The division of financial gain between taxi license owners and taxi drivers is the key question. Ultimately, if there is no cap on licenses, the value of the licenses will fall to zero. Drivers may then need to pay companies for dispatch services and the like, but they won’t pay anything for the privilege of driving a cab. That seems like a huge gain for them.

April Boutillette Brinkman

This is an extremely insightful article, I had not thought a lot about the issue of taxis in Portland. I am one of those automobile users I have to say, and am still sweltering over my $50.00 parking ticket from yesterday! I remember fondly living in San Jose, Costa Rica and I survived taking taxis everywhere. Talk about the wild west and one time I remember a taxi driver taking out a machete to show me and the passenger I was with how he protected himself. In a place where public transportation was few and far between and a lot of people did not have cars it was a good way to get around.

John Reinke

I was surprised that the article didn’t touch on the environmental impact of all those additional taxis in Seattle. Wouldn’t that necessarily be negative?

If we’re going to allow additional cabs, could we insist that only high-mileage vehicles (such as the Prius) be permitted?

On another matter, I cut-and-pasted the link to this article into an email to a friend of mine who is a transportation expert. This would have been easier to do if there were an email button somewhere on the page that I could have clicked on. Any chance of implementing that?

Alan Durning

Thanks for your note, John. You should find the icon of an envelope in the lower right of the article. That should let you send an email directly from our site. Thanks for sharing it!

Vince may have more to say about the environmental question, but we have written about the fuel economy of taxicabs before: http://www.sightline.org/?p=884

In general, though, taxis allow people to leave their car at home for a lot of trips. One taxi trip often substitutes for a whole bunch of other car trips. So the extra environmental burden of extra taxis is massively outweighed by the avoided driving that they allow.

Vince Houmes

We started the article with the assumption that a lot of cities are already working on greening their cab fleets, and take it as a given that more cabs would unlock greener choices for a lot of people. The math on this is not 100% clear to me, but I bet it’s not far off.

One way regulators could encourage a greener taxi fleet — that I’ve never heard discussed — is offering more licenses or lower fees to taxis that get better mileage, and/or have a better ratio of passenger miles to cruising miles. Taximeters can already track this info, but one would need to craft a policy that would encourage good practices and avoid those who’d try to game the system.

Taxi law

The Clean Air Act and Energy Policy and Conservation Act have, ironically enough, been interpreted by federal courts to preempt local efforts to directly regulate taxis on the issues of emissions or mileage. Cities like NY have continued to try to find a way around it, but courts have continued to strike down anything that looks like a mandatory regulation, including a de facto mandate imposed through steep incentives for better fuel economy.

Matthew 'Anc' Johnson

One thing to consider is that a taxi trip as opposed to a auto trip requires no storage at the destination. How much of our city is given up for parking?

Matthew 'Anc' Johnson

That should be personal auto…

Matt the Engineer

Great article. I’d also love to see a good environmental comparison, but it must make a car-free lifestyle easier.

I’ll throw another shout out to have 4-stroke or natural-gas-powered auto rickshaws in downtown areas (and only allowed on surface streets). They have a very low cost to entry for drivers, cost less to run/maintain/fuel, take up less traffic and parking space, and are easy to just hop in and go. I suppose somewhere like Miami might be more appropriate to start this trend than our wet region, but plastic flaps can fix rain issues.

Rich Jackman

I used to live in Seattle without a car. My most common use of cabs was for late-night rides home from bars or theater, and grocery shopping. One of my motivations for getting (and keeping) a car was that getting a cab to take home groceries often took longer than walking to the store and doing all the shopping combined. The few cabs available preferred the more lucrative airport runs to a grocery shopper taking a short trip with a lot of bags. freeing up the supply of cabs would encourage a lot of urbanites to forgo that car purchase they’re considering.

Michael H. Wilson

A group I came across some time ago named Community Solution, as I recall, claimed that wide spread use of jitneys would lower urban pollution by 75% as I recall. I have no idea where they got their numbers or how, and I have to question them, I think 30% is more like it, but from a libertarian point of view opening the market is exactly what we need to do. First low income people are often the least likely to be able to financially maintain their vehicles adequately. Giving them an alternative such as ride sharing cabs, or jitneys, would provide them with an alternative. Secondly it wold improve the options for a number of demographic groups especially low income people, many who are elderly women and low income, part-time working mothers.

Vince Houmes

I’m unaccustomed to thinking like a libertarian, but I found myself feeling sympathy for them quite a few times while doing this research!

The taxi/jitney/towncar ecosystem is wildly diverse, and I feel like I’ve only begun to understand the taxi side of things. It would be terrific if jitneys were able to provide the kind of benefits you describe, but Seattle at least is quite a ways from making that a reality.

Vince Houmes

Comment from a friend who lives in DC:

“D.C. is well known for having a regulatory regime that’s generally hostile to small businesses. But every so often, the city gets something right, and taxi policy is one such area. You’ll be interested to learn that the local taxicab companies have made a concerted push to introduce a medallion system to Washington. Indeed, the FBI went after a large number of Ethiopian cab drivers who attempted to bribe the former taxicab commission chair a few years ago — I think they formally charged upwards of a dozen drivers. The U.S. Attorney’s office is prosecuting a city councilman’s former chief of staff who took bribes from purported cab drivers.

Speaking strictly as a consumer, it’s easy to get a cab in D.C. at any hour of the day or night, especially in my neighborhood. I’ve caught cabs at 4:00 a.m. on a Wednesday, for example. Fares are reasonable and cabs are generally plentiful, which is indeed a marked contrast to Portland and Seattle. It’s a boon for those of us who don’t own a car and a way to create jobs where there is a demand for services.”

Kari Chisholm

I’ve noodling over this with a few friends on Facebook.

One challenge is that if you dramatically increase the number of taxicabs, you’ll get massive opposition from cab companies – who tend to be very powerful political players in restricted-taxi towns like Seattle and Portland.

A second challenge is that if you add enough cabs that they’re not hopping from fare to fare, you end up with pollution from idling cars.

Seems to me that there’s a single solution that solves both of these problems simultaneously: You simply tell each cab company that they can trade in each of their medallions and get two in return — provided that the two new medallions are for hybrids or electrics only. They’d get them for free, effectively doubling their ability to make money.

If Seattle medallions are going for $100k, then getting a free medallion for the price of buying two hybrids is a great deal for the cab company.

That also has the added benefit of phasing in the new medallions as cab companies have to get the financing for all the new hybrids they’re buying – so you’re not just dumping a bunch of new medallions on the market overnight.

Thoughts?

Vince Houmes

Interesting idea, Kari. I think that the medallions are owned by a mixture of individual drivers and cab companies, so there may not be a uniform response to that proposal.

If the new medallions were nontransferable, that would be a step in the right direction, too. Portland has a rule that medallions remain city property, and can’t be sold. By making the medallions a public property and not a private one, Portland has given themselves more flexibility; license “owners” there don’t have such a powerful incentive to resist changes.

stacy anderson

All Seattle companies, except for one do not own their medallions. In Portland the company owns the licenses, but not the cars as a rule. Also with the streetcars and Max light rail in Portland a lot of folks not got rid of the second car, but the first as well. Taxi use increased.

Nathanael

Oh my goodness that is important. In oil leases on federal land, they’re *supposed* to expire after 20 years, but they get repeatedly extended on a no-bid basis at below market prices (for upwards of 100 years so far) because they’re treated like transferable property. Turning artificial cartels and monopolies into *transferrable property rights* creates a giant lobbying group deeply devoted to keeping these monopoly privileges as a private privilege. It is frequently a disaster for democracy.

When the government-granted monopoly or cartel is nontransferrable, it is much easier to break the monopoly using political means, because the lobby for the private monopoly scheme is much smaller — it doesn’t include people who “might buy one of those some day”, like it does with transferrable schemes.

t.a. barnhart

your commentary ignores Las Vegas: many more cabs than Pdx AND higher costs. SF, Atlanta & Boston: more cabs than Boston yet their costs are either higher or only moderately lower. there’s no pattern to the data. and there’s nothing in the data that speaks to the presence/impact of public transportation. the number of people in Pdx who bike & do so as part of their nightlife: nothing there in the data. DC’s an anomaly, with its geography (govt centers surrounded by areas perceived as crime-infested) and the number of people who use cabs to get to the airport or a train station: that’s not in your data. in short, these 2 charts clarify nothing. this is not data anyone can make any realistic conclusions from other than more study is needed. and better data. much better data.

Vince Houmes

You’re right, it’s a complex issue that can’t be fully captured in a few charts. Taxi boards set prices in Boston, Las Vegas and Atlanta, too, so supply and demand don’t have a clear relationship with the prices.

In this short article I don’t mean to prove that lifting price and license caps will create a transportation paradise. I’m just exploring the oddness of the way taxis — unlike many other industries — are regulated. I do think that the Washington DC example suggests that more cabs would bring the price down; but it’s a complex task I wouldn’t attempt here hash out all the variables that would allow an apples-to-apples comparison between cities of very different characteristics.

t.a. barnhart

1st, thanks for replying Blogtown. it’s a good blog for an alternative newsweekly.

2nd, you know that charts like you have here will become the facts in many people’s minds. this can be a good thing when they are comprehensive and reflect a full set of relevant facts. yours do not. as i wrote, they raise more questions than they answer – but both your article & many of the responses suggest the charts actually capture more than bits of data that are missing way too much to be useful. not really useful, i think.

Red Diamond

There are presently 10 taxi companies in Portland applying for some 255 new taxi permits. Taxi companies would like nothing more than to acquire new permits. Why? Because each new permit translates into a new cab on the streets. And each new cab brings an average of $45,000 of annual revenue to the taxi companies. That’s what cabdrivers pay to lease the cab, also known as “the kitty”. The kitty includes dispatch and office services and insurance. It may or may not include vehicle ownership and maintenance, and it certainly doesn’t include gas.

It’s important to understand that cabdrivers – unlike Pizza Hut drivers – are not salaried employees. Put more taxis on the streets and each driver will make less money. Many drivers already make the equivalent of less than minimum wage, with no unemployment or healthcare insurance, workers compensation, medical coverage or retirement plans. To make ends meet, most drivers work upwards of 80 hours per week. Many work more than this even though Portland limits working hours to “only” 14 per day.

There are complex yet legitimate reasons why you wouldn’t want to subject the taxi industry to free-market anarchy. Things would get ugly mighty fast. And each city has its own historic and contemporary particulars that make across-the-board comparisons challenging to apply. See http://www.cabdriversalliance.com for some relevant perspective. Meanwhile, simply adding taxis without a corresponding plan improve the economic realities of taxi drivers is cruel and counterproductive. Please do a LOT more looking before you leap.

Red Diamond,

Taxi Driver’s Representative, Portland, OR

Asher

Do you ever think that if there is more cabs on the streets and lower prices that more people will take them?

Also a cab driver is choosing his job. If he knows he needs to work 80 hours to make ends meet and doesn’t like it, then find another job.

When I take a cab, I’m not doing that to support his family, I’m doing that because I need to get somewhere.

Nathanael

OK, here are several much better proposals for the problems you describe:

(1) Require that taxi drivers who do not own their own cabs be treated as employees of the cab owner/dispatcher. Can be done at the state level. The current system seems tantamount to a number of the “we’re going to pretend you’re not an employee” scams which have been busted by the IRS so many times.

(2) Have the city take over all dispatch. It’s a natural monopoly anyway. Then charge a lower fee for it.

(3) Make sure the insurance market offers reasonably-priced insurance to good drivers. There are state insurance regulators for that…

Government mandated price-fixing isn’t the best solution to the problems you describe…

Carl Iverson

In answer to the chart, correlation does not imply causation. Houmes could’ve used the color of cabs set against the gender of the driver and it would yield the same meaningless results. As for Sightline’s whole argument, it’s a nifty rhetorical trick called a fallacy of many questions:

A) Taxicabs can’t provide me with immediate service.

B) I need immediate taxicab service.

C) Therefore I need more taxicabs willing to provide me service.

Vince Houmes is asking a question that cannot be answered without admitting a presupposition that may be false. Houmes and Sightline both need to look closer at what can make service run more efficiently. For Portland’s two largest taxi companies, Broadway and Radio Cab, the use of technology that puts the customer in direct contact with the driver is proving to be a much more effective means of streamlining dispatch and cutting down on drivers chasing orders outside their immediate vicinity. The Taximagic smart-phone application serves this purpose well and is in use at both companies.

I’m concerned that a think tank that positions itself as one tasked with exploring issues of sustainability would immediately leap to a conclusion that simply calls for more of anything over a means of access made more efficient.

Kari Chisholm

The TaxiMagic app is, in fact, amazing.

I do think, however, that it represents an interesting next-evolution in the taxi economy. As Red Diamond notes, the cab companies take a huge chunk of the revenues earned by individual cap drivers.

But a large part of their control relates to the ability to deliver dispatched riders to those drivers. If an app can do the same job, without requiring a central dispatcher, then there are fewer reasons for cab companies to exist. (There are still some, chief among them the financial investment required to buy a cab.)

Right now, TaxiMagic works through the existing dispatchers, but it won’t be long before that app – or one like it – does what nearly all internet marketplaces do: disintermediate the system, or “kill the middleman”. One can easily imagine an app that broadcasts fares directly to the nearest available cab, skipping the big dispatch center entirely.

Nathanael

Mind you, the person selling the app and the cab-side software will make a killing….

Josh Mahar

From a liberty and efficient market standpoint, most certainly we should do away with our anachronistic licensing system.

But on environmental grounds I think we honestly need more data. Intuitively it seems like better access to cabs is greener but realistically cheaper fares could pull riders from public transit or walking just as much as from SOVs. Simply looking at your graphs, I see low fares and large cab volumes in both stereotypically eco and non-eco cities.

It would be good to explore how transit patterns actually shifted, if at all, in a place that went from regulated to deregulated.

Alan Durning

That’s a tall order, insofar as most cities haven’t switched from medallion to non-medallion. Most reforms are much more modest than that.

What we do know is that the world’s transit capitals (including DC, along with London, New York, etc.) are also very heavy taxicab users. There’s more synergy.

Marshall

More RadioCabs would be great. More of any other company’s cabs would not. The service from any other company in town, like from the airport or Amtrak, is downright hostile. Terrible.

Japhet

This is one arena where technology can circumvent the anti-competitive, anti-sustainability practices of the taxi companies and medallion systems. Uber Cab for instance, is a private car service that adds convenience, quality service, and competes at the high-end. https://www.uber.com/

Imagine if there were a more bare-bones version that allowed private individuals to get approved, vetted, rated and secured like Zebigo but for hitch-hiking, carpooling, etc. Then you have a new, competitive, efficient mechanism to allocate passengers to vehicles, allow entrepreneurs into the marketplace, and get people where they need to go.

j